Why do many firms fail to achieve their ambitions and growth targets in revenue and profitability? Several reasons can be found and one of the fundamental issues lies with the firm’s leadership not being able to articulate its competitive strategy and communicate it down to the operational levels of the organisation.

A lack of clarity about a firm’s competitive strategy results in poor execution. Why? People in the company have no sense of direction and therefore cannot align themselves with a common purpose. Worse still, in some situations firms have only operational strategies and attempt to survive on a year-on-year basis.

The majority of firms lack value-creating and uniquely different strategies. Competitors converge on similar strategies competing on similar platforms, eventually leading to eroding returns. They fail to address the core of how value is created and captured by the organisation.

One of the hallmarks of successful companies is sound alignment between strategy and execution. Hence, it is important to articulate your strategy in a simple yet meaningful way so that the whole organisation shares a common direction and purpose.

Let’s look at a typical scenario. It is the third quarter in the financial year. The setting is the boardroom where the directors meet to proceed with their structured monthly meeting. Last month’s performances and the cumulative figures are evaluated. Our revenues are not on target, neither is our bottom line, says the Chairman. We are behind our budgets. Looking at the trend, we will end the year behind our budgets. What do we say to our shareholders? We cannot allow this trend to continue, responds another board member. Last year too, the team failed to meet its budget. Even though we ended up with a profit, we were far behind our targeted figures.

The Finance Director then provides an analysis of the financials and comparisons vis-a-vis budgets, both for the current years and for the previous year. A lengthy discussion follows. The final conclusion is that we need to strengthen our strategic planning process. Obviously, our team is not competent enough to draw up the right strategies to achieve the agreed upon targets. Let’s hire an external consultant and facilitate the process for next year.

Sounds familiar? This is one of many such scenarios that take place in firms that struggle to keep pace with changing market dynamics.

So, what follows? A consultant is hired or sometimes a senior member within the organisation is designated to review and carry out a fresh strategic planning process. The process is planned, a retreat arranged, where select team members are taken on a weekend residential workout. The process begins by taking stock of the external environment followed by an assessment of the firm’s capabilities.

The discussion is followed by an analysis which concludes with a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis. Presentations are made by groups, challenged, debated, discussed and agreements reached with amendments. Great! There is a long list of findings that appear in the SWOT analysis. Everybody is happy and proud of their findings. Now comes the next step – let’s set goals for the next financial year.

With deliberations over, the groups present their goals. Again, the same process is adopted, namely challenging, deliberating, negotiating and eventually agreeing on some lofty goals. There are examples galore to increase sales, increase market share, reduce costs, increase profitability, improve staff motivation and so on.

Then comes the next step and perhaps the more important aspect in the minds of the team – strategies to achieve the objectives that have been agreed upon. A comprehensive list of strategies is articulated, with attention paid to novelty and creativity in most instances, to impress senior management. You can label some of these as fantasies rather than realistic steps.

Once this process is completed, the onus is on the finance division to put together the budget for the next financial year for presentation to the Board. What follows is a negotiation process between the Board and the CEO and his senior management team. Whilst the Board will try to push the figures up and question the validity of some numbers, actions, etc., the management team will defend its position with justifications. Finally, agreement is reached (after a process of horse-trading) and the team is wished good luck to achieve the said budget.

The result in the next financial year, more often than not, is nothing different than that of previous years. Justifications prevail, slack market conditions, a terrorist attack, competitors dropping prices, lack of a product range vis-a-vis competition and so on.

Why is there a gap between intent and realisation?

The term strategy used in your strategic plan and the competitive strategy of the firm bear two different contexts and mean two very different things. Unfortunately, most executives are unable to distinguish between the two. Thus, when you question executives as to what the strategy of the firm is, different people have different interpretations.

Some say we are following a “cost-reduction strategy” or “our strategy is to increase market share by 15%” or “our strategy is to go international” and so on. Others generalise it. They say “our strategy is to achieve our stated objectives and for that we have several” and then begin to list all of them. Correct. But when they are confronted with the question “what is your firm’s competitive strategy?” the response is most often a blank stare. Sometimes I ask the same question in another manner – why should a customer buy your product or service and not that of your competitor? The typical responses for these include “our products are of a higher quality”; “we give a better service”; “we have financial stability, a strong brand, motivated staff” and so on. All these are generic answers that are copied from textbooks. Yet when they are confronted with the questions, “what do you mean by high quality?”, “what is better about your service?”, “can’t your competitor also match your service levels?” or “can any firm that is financially unstable be in business?” they struggle to find justifiable answers.

The term strategy used in your strategic plan and the competitive strategy of the firm bear two different contexts and mean two very different things. Unfortunately, most executives are unable to distinguish between the two. Thus, when you question executives as to what the strategy of the firm is, different people have different interpretations

The problem lies with executives’ views on strategy. All businesses have a competitive strategy by default, though not necessarily one that makes the firm stand out from the rest. Not knowing what exactly your strategy is, is one problem and not knowing how to articulate it is another, though there is a close link between the two. For a firm to articulate its competitive strategy, the firm’s blueprint, one needs to know its critical components. It is therefore the responsibility of the firm’s leadership to communicate the same in a lucid manner so that everyone in the company is headed in one common direction; all actions planned to execute the strategy reinforce each other in a cohesive manner.

Constituents of a robust competitive strategy

Michael Porter in his seminal article ‘What is strategy?’ (HBR Nov-Dec, 1996) lays out the characteristics of what strategy should encompass: creation of a unique and valuable position, involving a different set of activities, choosing what not to do and creating a fit with the ways the firm’s activities interact. However, in the real world a firm should be able to clearly articulate the competitive strategy it follows, that is explicitly stating how it creates and captures value, brings about added value to the market and how it stands to make such differences.

Several scholars (Eric Van Den Steen, Adam Brandenburg, Donald C. Hambrick and James W. Fredrickson et al) have put forward different propositions as to how a strategy should be articulated; diverse but with a few common threads as well. Together with such knowledge and taking into account the practice of strategy, I have put together an outline of what a ‘Strategic Blueprint’ of the firm must therefore incorporate at minimum: the purpose, strategic goals and priorities, strategic positioning, value proposition, competitive advantage and directional methods. Let us now examine each one of these components in that order.

Purpose

The purpose of an organisation articulates the fundamental reason for its existence. It espouses a ‘purpose’ beyond simple profit maximisation. The purpose of an organisation does not answer the question ‘What we do?’ which is typically products and services, but rather answers the question ‘Why we do what we do?’. Such purpose should be inspirational and motivational to galvanise people to spark long-lasting positive change, driving growth and innovation. It is the cause that defines their contributions to society at large.

A classic example is IKEA’s purpose (they define it as their concept). They articulate it as “to create a better everyday life for the many people”, and how do they go about doing this? “By offering a wide range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.”

Strategic goals should be expressions as to what your business intends to achieve in the medium to long term. Such goals should reflect the intended accomplishment of the strategy of the firm. They should be measurable and time-bound and must be stated explicitly. Such goals can be stated in terms of profitability, growth and risk

It is simple, directional, justifies its existence and is moreover inspirational. Here’s another example of a purpose statement that I articulated for a local firm operating in the agriculture industry: “To enhance the living standards of our farmer community.” How do we go about doing this? Through “leadership in marketing and service, creating exceptional customer loyalty by offering products or services of appropriate technology and of superior value that will enhance the farmer’s productivity.”

Cynthia Montgomery of HBS (The Strategist) posits that a meaningful purpose should state why it exists, the unique value it brings to the market, what sets it apart and to whom it matters. A well-articulated purpose, she argues, is not only enabling but also sets the stage for greater value-creation and capture. This in my view is the starting point for any organisation.

Strategic goals and priorities

Strategic goals should be expressions as to what your business intends to achieve in the medium to long term. Such goals should reflect the intended accomplishment of the strategy of the firm. They should be measurable and time-bound and must be stated explicitly. Such goals can be stated in terms of profitability, growth and risk.

Strategic priorities will focus the firm’s attention on limited but important areas to be achieved for the strategy to be successful. Such priorities must be externally focused and should emphasise areas such as target customers, target markets, evolution of the competitive formula, current and future proposition and the build-up of strategic capabilities to meet emerging changes.

Strategic positioning (Landscape)

Strategic positioning is about identifying the right plateau on the business landscape that optimises the opportunity for the firm to enhance its profitability. Identifying and occupying such plateaus require a right strategy, one that exhibits a coherent whole. Finding such plateaus is no easy task.

A careful analysis of different customer segments, their respective needs, geographical scope, alternate business models, extent of vertical integration required and evaluation of the impact of the different structural forces of the industry together with the competitive forces will show the firm the prospective spaces available for occupation. Thus, what the firm is left with are the choices, from which it has to decide on a select few.

A set of integrated core choices will showcase what the firm has decided to do as well as what it has decided not to do. These core choices must be stated explicitly in your ‘blueprint’ and form the very basis of the firm’s strategy.

To illustrate; Southwest Airlines focused on customers who needed shortfall flights and were price-sensitive and decided to offer only one class of service (economy only), not to serve any meals, point-to-point travel (no connections), higher frequency, flights out of secondary airports and no assigned seating. For each of the choices that Southwest selected, they had an alternative (look at the opposite of each choice selected) which they chose not to do. To deliver the selected choices, they developed a business model that was totally different from the normal hub and spoke systems that the traditional airlines followed. All of the choices made by Southwest led to its derived competitive advantage, of keeping absolute costs low.

Value proposition

The value proposition will reflect the firm’s sum total of offerings and experiences delivered to customers during their interaction with the company. It reveals how the firm’s product or service is different from their competitors’ and highlights the benefits of such a product or service crystal clear from the very outset.

A compelling value proposition must capture:

- Target market

- Value (benefits)

- Offering

- Differentiation

- Proof

Competitive advantage

In this segment, the firm must identify which of the choices drive its competitive advantage. Arising from the core choices selected by the firm, the company’s activities interact and reinforce one another in a manner that drives its competitive advantage. It is these activities that determine how much value is created and captured by the firm.

The stock of knowledge and know-how resulting from these interactions over a period of time, which are difficult to be imitated, reside within the firm and become valuable over time when leveraged. This stock of resources and capabilities, which are long-lasting and unique, must be treated as strategic assets of the company. Such strategic assets must be explicitly stated since they require constant nurturing and development to meet the future challenges of the firm.

Broadly, the following resources and capabilities can be classified in relation to the competitive advantage. Though not exhaustive, it is meant to be used as a guideline for identifying advantage-driving resources and capabilities that are company-specific and unique and inimitable.

Resources:

- Unique property (E.g. assets with locational advantages)

- Intangible assets: Brands, patents, proprietary recipes or formulas, etc.

- Locked-in or preferred relationships: Customers, suppliers, complementors, channel partners and any other important stakeholder

Capabilities:

- Innovative, design capabilities

- Specialised individual skills, know-how and competencies in carrying out specific tasks

- Overall organisational systems, processes, leadership and culture

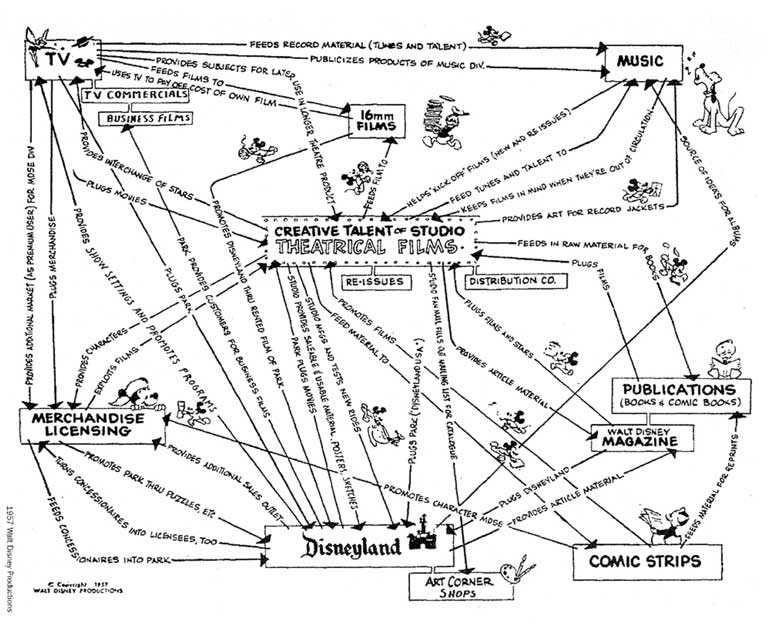

A complementary approach to identify strategic assets and their interactions is to map the firm’s landscape of value creation. Such a map will have to be drawn from existent knowledge and then developed to a stage to identify potential valuable configurations of resources, capabilities and interactive activities.

The starting point will be to identify the firm’s distinctive core competency, a competency that distinguishes the firm from its competitors.

Todd Zenger (HBR, June 2013) illustrates this with the classic example of Disney’s value map which Walt Disney had apparently created in 1957 and later found in their archives. It shows how Disney’s core of creative talent of studio interacts with strategic assets such as publications, a theme park, merchandising and music to create immense value to an organisation.

Directional methods

The final section is to evaluate the means of attaining a desired state, whether it is a specific geographic scope, product category, value-creation process, market segment or combination of these decisions, given the strategic assets the firm possesses as well as what it should possess in the future. Such routes will include decisions on:

- Organic growth

- Alliances

- Licensing/franchising

- Acquisitions/mergers

Conclusion

With clarity on the strategy pursued, two things happen: Firstly, formulation becomes infinitely easier because executives know what value they have to create. Secondly, implementation becomes much simpler and more effective because the essence of the strategy can be easily internalised by everyone in the organisation.

As much as I have attempted to simplify the core content of a ‘Strategic Blueprint’ of a firm, I have chosen not to oversimplify the content either, because the leadership of the company must have a strong handle to steer its strategic direction. It pays to invest a fair amount of time and energy in crafting a robust strategy for the firm, how it combines its industry assessment with the firm’s strategic assets to create and capture value. Capturing this competitive strategy in a meaningful way is the ‘Strategic Blueprint’ of the firm.

Last but not the least, we must avoid calling everything strategy. When we do so, what we end up with is a series of strategies, which creates confusion and undermines their own credibility. Strategy should not be used as a catchall term to mean whatever it is meant to be in organisations.

(The writer is a Consultant Strategist and specialises in strategic thinking, growth management, leadership, change and international trade. He is a Senior Fellow of the Institute of National Security Studies of Sri Lanka. He can be reached at lasantha@strategynleadership.com)